A caution against ephemeralization

These days I derive little joy from my possessions of necessity. Knowledge workers, over the last couple of decades, have traded the engagement of our senses for an upgrade in flexibility. I shall elaborate.

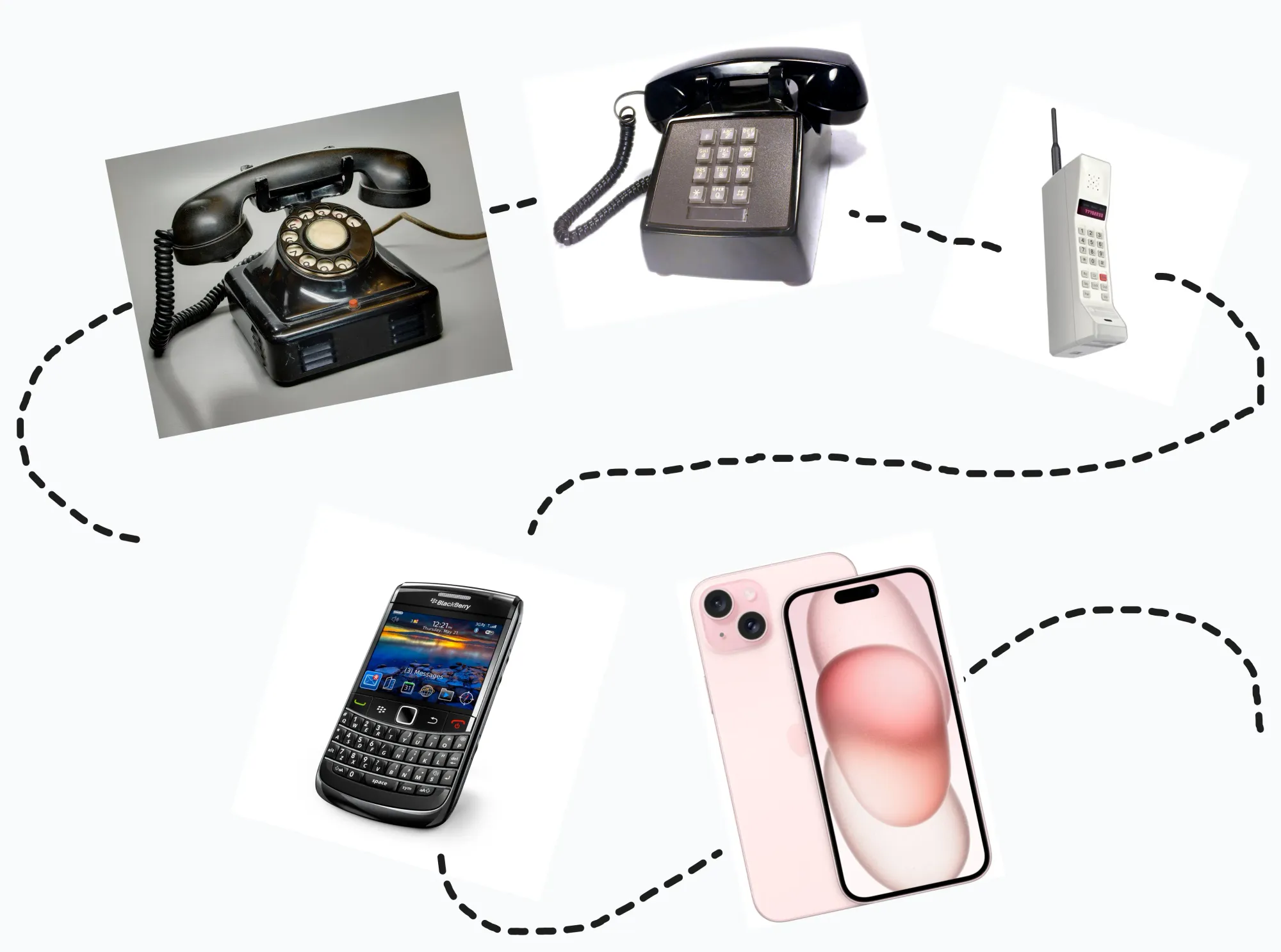

Let's take a phone. Here's a rough chronology.

Notice the gradual loss of visual, tactile and sensory stimuli (henceforth dimensionality) in the experience of making a phone call. A smartphone is a relatively easy example to pick on. But this is true of many other possessions and their "modernised" counterparts.

| High dimensionality article | Lower dimensionality modern "evolution" |

|---|---|

| Buttons, Gauges, Dials, Sliders | Touchscreens, Capacitive Buttons |

| Physical Books | Audiobooks, eBooks, Websites |

| Pen and Paper | Text file, Note-taking apps |

| Typewriters | Touchscreen keyboards |

| Paper Money | Digital Payments/UPI |

| Fish Market | Licious |

| Mango | Maaza, Slice, Tropicana |

| Glass bottle coke | Plastic bottle coke |

| Morning jog | Treadmills |

| Sports, Board Games | Video Games |

| Theater | Cinema |

| Fireplace | Indoor Heaters |

| Working in an office | Remote work |

| Live Music, Record Players | mp3s, Spotify |

I have seen a desire for higher-dimensionality articles dismissed as paranoid technophobia or an irrational longing for the past. There have also been arguments in favour of intentionally moving to low dimensionality—here's Marc Andreesen quoting futurist Buckminster Fuller, on the topic of ephemeralization:

Technology lets you do more and more with less and less until eventually, you can do everything with nothing.

Actually, the above is likely a misquotation. The only occurrence of this quote in my research is Marc's website. I could not find any such passage in Fuller's book where he introduces and discusses the term ephemeralization. But I digress.

My point is that we must consider the costs of ephemeralization. I believe that a prerequisite for a well-examined life is to, as much as possible, be present with the raw sensation of experience. That's why it's important to design things that engage with more channels of sensory reception, especially in ways that ground the user to the present moment. It's a subtle human need. This low dimensionality of modern technology is why there's some innate resistance and a lack of joy in their use (excluding some short-term dopamine bursts).

Yet, the considerations of scalability, economic optimisation and extreme convenience will always win over this subtle, unmeasurable and "unjustifiable" characteristic of "low engagement of human sensory experience". And I wouldn't say it's a good idea to pick the left column in my table every time. I am not anti-technology.

But consider the things in the left column anyway. There's a huge loss in the dimensionality of articles in the modern world. I hypothesise that if everything loses dimensionality eventually, there will be a point where the increasing deprivation of sensory stimuli in the things we use will reach a threshold at which most people will feel terribly joyless and incomplete. And no one will be able to pinpoint why. The second and third-order effects from the lack of being grounded in the present felt experience would have something to do with it.

If you are a product designer or technologist—consider creating articles that somehow make up for this deficiency.

Rematerialisation Rituals

I don't find a lot of joy in using some of our modern marvels. Broadly speaking, I dislike my phone, I don't like using most software, and I can't work remotely all the time. I have found myself compensating for the increased dematerialisation of the world with some rematerialisation rituals. I don't always do all of these rituals regularly, but including just a little bit of these in my life has (in my head) helped with some background feelings of wellness. Here are some of them:

- Mindfulness, which helps extract more out of low-dimensionality articles.

- Working from a co-working space (as a remote worker).

- Going out over staying in.

- Hobbies that don't involve digital devices.

- In my case, it's coffee brewing. Better yet, I also grind the beans by hand.

- Cooking is also a good rematerialisation hobby.

- Buying physical books over eBooks.

- Taking notes on pen and paper.

- Developing a discerning palate.

- Investing in colour and texture—for clothes, rugs and articles that are often used.

Appendix: A narrative about a smart thing Apple did to wean people off their instinct against low dimensionality

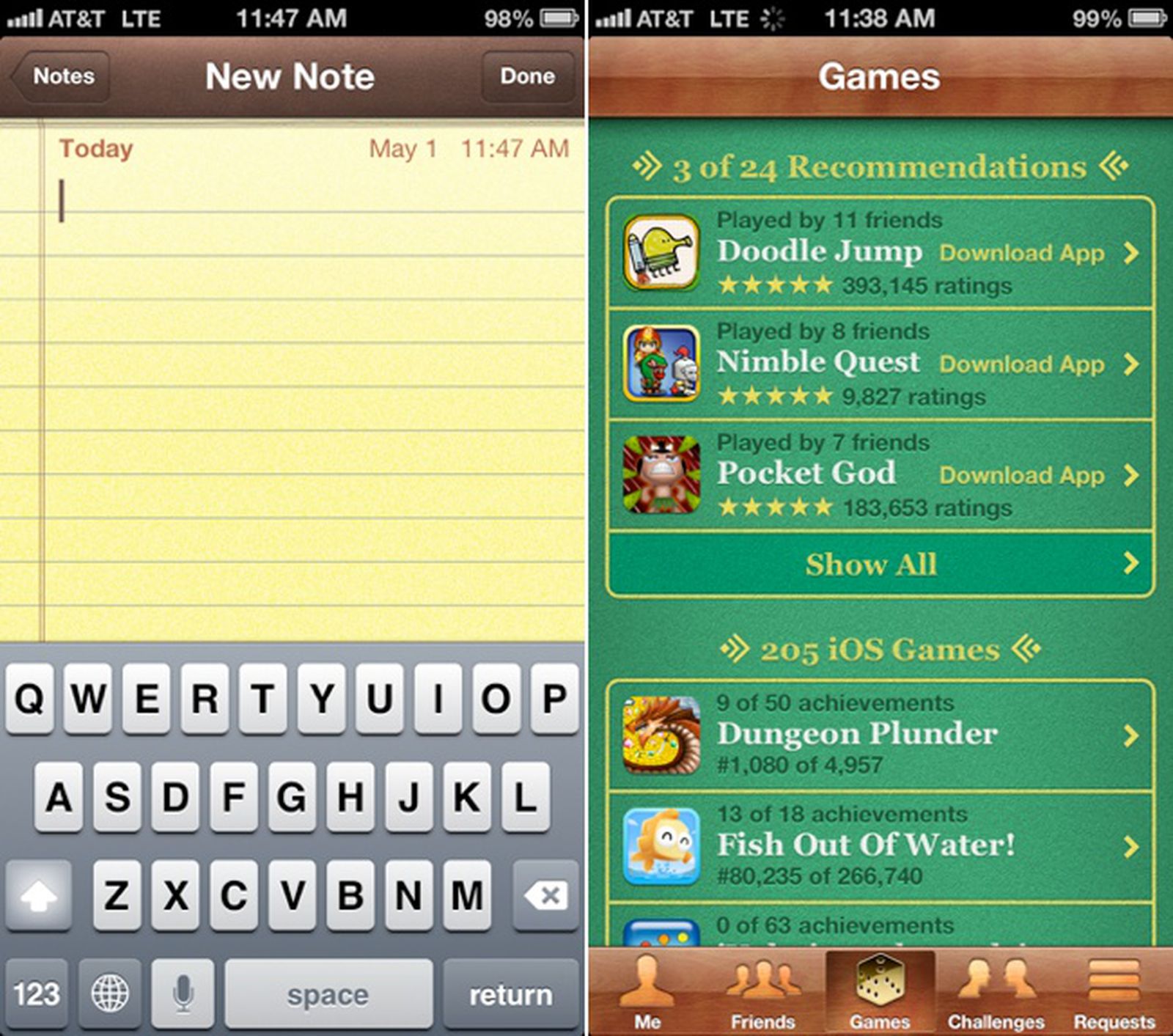

Pure speculation, but allow me to weave this narrative. I'd say Apple's iPhone was a big driver that moved a lot of people's waking hours into low-dimensionality activities. The number of things one could do on this flat, buttonless, low-tactility panel was unprecedented. It might have been uncomfortable too, in a world that wasn't used to this level of dematerialisation.

But Apple's UI designers provided a bridge from the highly material to the highly ephemeral world to ease this transition. They made a lot of the early apps and interfaces skeuomorphic—it's an old design trick where the designer carries some familiar elements of older technology onto a new medium. All the fake wood and leather, although a poor imitation of the real thing, did its job.

This surely would have helped make the transition less jarring. Eventually, these elements were stripped away once the visceral barrier had been overcome and people were enjoying the conveniences and power of the modern smartphone.